La nature de la blessure

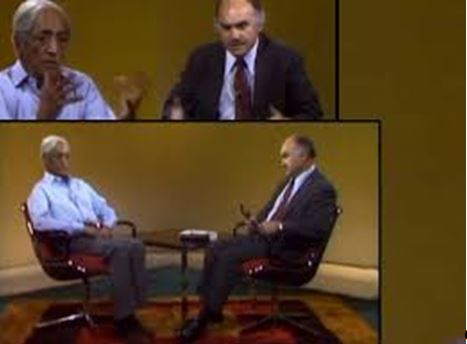

J. KRISHNAMURTI

Onzième entretien

avec

Allan W. ANDERSON

25 Février 1974

Université de SAN DIEGO - Californie

« « « Transcription » » » de la vidéo réalisée par copie et assemblage des sous-titres de la traduction en français. (août 2015) : (Voir la vidéo en suivant ce lien :)

http://www.jkrishnamurti.org/fr/kri...

J. Krishnamurti naquit en Inde du Sud et fut éduqué en Angleterre. Il donna pendant des décennies des conférences aux Etats-Unis, en Europe, en Inde, en Australie et ailleurs dans le monde. Le travail qu’il effectua au cours de sa vie le conduisit à répudier toutes attaches avec les religions organisées et les idéologies ; il a déclaré que son unique souci était de libérer l’homme absolument et inconditionnellement. Il est l’auteur de nombreux ouvrages, dont L’Eveil de l’intelligence, le Changement créateur, Se Libérer du connu et Le Vol de l’aigle. Ce dialogue fait partie d’une série entre J. Krishnamurti et le Docteur Allan W. Anderson qui est professeur de théologie à l’Université de San Diego où il enseigne les Ecritures Indiennes et Chinoises et la tradition des oracles. Le Docteur Anderson, poète reconnu est diplomé de l’Université de Columbia et du Séminaire de Théologie de l’Union. L’Université de Californie l’a honoré en lui décernant le Prix de l’Enseignement.

LA NATURE DE LA BLESSURE

A : Monsieur Krishnamurti, une chose m’a paru ressortir de nos entretiens avec une grande force. D’une part, nous avons parlé de la pensée et du savoir en termes d’une relation dysfonctionnelle à cet égard, mais vous n’avez jamais dit que nous devrions nous débarrasser de la pensée et vous n’avez jamais dit que le savoir en tant que tel a profondément à voir avec cela. Cela soulève la question du rapport entre intelligence et pensée, et de ce qui maintient un rapport créatif entre l’intelligence et la pensée, peut-être quelque activité primordiale durable. A la réflexion, je me suis demandé si vous seriez d’accord sur l’hypothèse que peut être, le concept de Dieu est apparu dans l’histoire humaine comme une émanation de cette activité durable, concept dont il a été fait un bien mauvais usage. Ceci pose toute la question du phénomène religieux lui-même. Je me demande si nous pourrions en discuter aujourd’hui.

K : Oui. M. Vous savez, des mots comme « religion », « amour » ou « dieu » ont perdu presque tout leur sens. Il y a eu un énorme abus de ces mots, et la religion est devenue une vaste superstition, une grande propagande, des croyances et des superstitions incroyables, une adoration d’images faites de la main ou de l’esprit de l’homme. Donc, quand nous parlons de religion, j’aimerais, si vous le permettez, que nous soyons bien clairs sur le fait que nous nous y référons dans son véritable sens, et non dans celui des chrétiens, hindous, musulmans ou bouddhistes, ou de toutes les stupidités qui ont lieu au nom de la religion. Je pense que le mot « religion » signifie rassembler toute l’énergie à tous les niveaux - physique, moral et spirituel -, ce rassemblement d’énergies devant entraîner une grande attention. Dans cette attention, il n’y a pas de frontières à partir desquelles on procède. Pour moi, le sens de ce mot est : rassembler la totalité de l’énergie afin de comprendre ce que la pensée ne peut saisir. La pensée n’est jamais neuve, jamais libre, elle est donc toujours conditionnée et fragmentaire comme déjà dit. La religion n’est pas une chose créée par la pensée ou la peur, ni par la satisfaction des plaisirs, au contraire, elle est bien au delà de tout cela, n’étant ni romantisme ni croyance spéculative, ni sentimentalité. Je pense que si nous pouvions nous en tenir à cette acception-là, en écartant toute l’ineptie superstitieuse qui se poursuit dans le monde au nom de la religion, qui n’est qu’un cirque, si beau soit-il, nous pourrions alors commencer à partir de là, dans la mesure où vous acceptez d’user de ce mot dans ce sens là.

A : Pendant que vous parliez, je pensais à la tradition biblique selon laquelle certaines paroles des prophètes semblent pointer vers ce que vous avez dit. Ainsi, Isaïe, parlant au nom du divin, disait : "mes pensées ne sont pas vos pensées, mes voies ne sont pas vos voies, autant les cieux sont élevés au dessus de la terre ; et mes pensées au-dessus de vos pensées, cessez donc de penser à moi, dans ce sens-là.

K : Oui.

A : Et n’essayez pas de trouver une voie vers moi que vous avez conçue car mes voies sont plus élevées que les vôtres. Pendant que vous parliez, je pensais à cet acte d’attention, ce rassemblement de toutes les énergies de l’Homme entier, le très simple, « Sois immobile et sache que je suis dieu ». « Sois immobile. » Il est stupéfiant de penser combien peu d’attention a été prêtée à cela, par rapport aux rituels.

K : Mais je pense que nous avons perdu le contact avec la nature, avec l’univers, avec les nuages, les lacs, les oiseaux ; c’est lorsque nous avons perdu contact avec tout cela que les prêtres sont entrés en action. Puis, toute la superstition, les peurs, l’exploitation, tout cela commença. Les prêtres devinrent les médiateurs, entre l’humain et le soi disant divin. Et, je crois que, si vous avez lu le Rig Veda - on m’en a parlé car je ne lis pas tout cela -, le premier Veda ne porte aucune mention de Dieu. On n’y trouve que cette adoration de quelque chose d’immense qui s’exprime dans la nature, la terre, les nuages, les arbres, la beauté de la vision. Mais les prêtres, devant tant de simplicité, dirent : "c’est trop simple ;

A : Compliquons-le.

K : Oui. Apportons-y un peu de confusion. Et cela commença. Je crois que l’on peut en retrouver la trace depuis les anciens Vedas jusqu’à aujourd’hui, le prêtre étant devenu l’interprète, le médiateur, l’explicateur, l’exploiteur, l’homme qui dit : ceci est juste, ceci est faux, il faut y croire, sinon vous serez perdu, etc. etc. etc. Il amena la peur, et pas l’adoration de la beauté, pas l’adoration de la vie vécue totalement, entièrement, sans conflit, mais quelque chose placée à l’extérieur, au-delà et au-dessus, qu’il considéra comme dieu, et pour lequel il fit de la propagande. Je pense donc que nous devrions dès le début nous servir du mot religion de la façon la plus simple, c’est à dire dans le sens de rassembler toutes les énergies de la sorte que dans cette qualité d’attention totale, apparaisse l’incommensurable. Car comme nous l’avons dit l’autre jour, le mesurable est le mécanique que l’Occident a cultivé, embelli technologiquement, physiquement - médecine, sciences, biologie etc., ce qui a rendu le monde si superficiel, mécanique, terre à terre, matérialiste. Et cela se répand dans le monde entier. En réaction à cette attitude matérialiste, naissent toutes ces superstitions, ces religions qui n’ont aucun sens, aucune raison, qui se perpétuent. J’ignore si vous avez vu l’absurdité de ces gourous venant de l’Inde qui enseignent comment méditer et retenir sa respiration ; ils disent : « je suis dieu, adorez- moi ». C’est devenu tellement absurde et puéril, tellement immature. Tout cela indique la dégradation du mot « religion » et de l’esprit humain capable d’accepter cette sorte de cirque, de stupidité.

A : Je pensais à un commentaire de Sri Aurobindo dans une étude sur les Vedas où il explique le déclin de cette philosophie. Il dit que celle-ci mise en paroles par les sages, échut ensuite aux prêtres, puis aux érudits et aux académiciens. Mais cette étude ne fournit aucune explication sur les raisons de la reprise par les prêtres. Et je me demandais pourquoi ...

K : Je pense que c’est assez simple, M. La façon dont les prêtres s’en s’ont saisi et toute cette affaire. Du fait que l’homme se préoccupe tellement de ses propres petites affaires et petits désirs mesquins, de ses ambitions, de toute cette superficialité, il veut quelque chose de plus, quelque chose de plus romantique, de plus sentimental, autre chose que la désespérante routine quotidienne de la vie. Il cherche autour de lui « venez par ici, j’ai les dieux », lui disent les prêtres. La façon dont les prêtres sont entrés là dedans me paraît très simple, vous le voyez en Inde, vous le voyez en Occident. Vous le voyez partout où l’homme commence à se préoccuper de la vie quotidienne, à gagner son pain de chaque jour, à se loger, etc. Il veut quelque chose de plus que cela. Après tout je vais mourir, il doit bien y avoir quelque chose de plus.

A : Fondamentalement, c’est donc la recherche de la sécurité, de ...

K : ... d’une grâce divine ...

A : ... qui le préserve de ce cycle désespérant de la naissance et de la mort. Vous dites qu’à force de penser au passé et d’anticiper le futur, il manque le présent.

K : Oui, exactement.

A : Je comprends.

K : Donc si nous pouvons nous en tenir à cette signification du mot « religion » nous sommes amenés à poser la question suivante : l’esprit peut-il être si attentif, de façon si totale qu’il se trouve face à l’indicible ? Voyez-vous pour ma part, je n’ai jamais lu ni les Vedas, ni la Bhagavad Gita ni les Upanishads, ni la Bible ni une quelconque philosophie. Par contre j’ai tout questionné.

A : Oui.

K : Pas seulement questionné mais aussi observé. Il en ressort la nécessité absolue que l’esprit soit totalement silencieux. Ce n’est qu’à partir de ce silence que l’on perçoit ce qui a lieu. Si je bavarde, je ne vous écouterais pas. Si mon esprit est constamment agité, je ne prêterais pas attention à ce que vous dites. Etre attentif signifie être silencieux.

A : Apparemment, certains prêtres se sont mis dans des situations difficiles à ce sujet, pour avoir, semble-t-il, saisi cette chose. Je pense à Maître Eckardt qui disait que « quiconque sait lire le livre de la nature n’a nulle besoin des écritures ».

K : C’est bien cela.

A : Evidemment, cela lui a apporté bien des ennuis vers la fin de sa vie et l’église l’a rejeté après sa mort.

K : Bien sûr, bien sûr. Une croyance organisée comme celle de l’église est trop évidente. Elle n’est pas subtile, manquant de véritable profondeur et de véritable spiritualité. Vous savez ce qu’il en est.

A : Oui.

K : Je demande donc ceci : quelle est la qualité qui permet à un esprit et, par conséquent, au cœur et au cerveau, de percevoir quelque chose au delà de la mesure de la pensée ? Quelle est la qualité d’un tel esprit ? Car cette qualité est celle d’un esprit religieux. Cette qualité d’esprit capable d’éprouver le sentiment d’être sacré en lui-même, et donc capable de voir quelque chose de sacré, au delà de toute mesure.

A : Le mot « dévotion » semble impliquer ceci, s’il est saisi dans son véritable sens. Selon votre propre phrase : « rassembler l’énergie vers une attention focalisée ».

K : Focalisée dans une direction ?

A : Non, je n’entendais pas par là une focalisation.

K : C’est ce que je me demandais.

A : Je voulais plutôt dire intégrée en elle-même, absolument silencieuse et indifférente aux projections mentales vers le futur ou le passé. Simplement là. Le mot « là » est également impropre parce qu’il suggère une localisation, etc. Il me paraît très difficile de trouver un langage qui reflète ce que vous dites, parce que les paroles s’expriment dans le temps, progressivement, reflétant une qualité qui ressemble plus à la musique qu’à l’art graphique. Un tableau se révèle d’emblée, tandis que d’écouter de la musique exige d’attendre la fin d’une phrase musicale pour pouvoir saisir l’ensemble du thème.

K : Tout à fait.

A : Le même problème se pose avec le langage.

K : Non, nous ne sommes pas, M., entrain de nous préoccuper de savoir quelle est la nature et la structure d’un esprit et par conséquent sa qualité qui n’est pas seulement intrinsèquement sacré et saint mais encore capable de voir quelque chose d’immense ? Nous parlions l’autre jour de la souffrance personnelle et la souffrance du monde ; ce n’est pas qu’il faille souffrir, mais la souffrance est là. Chaque être humain la subit terriblement. Et il y a la souffrance du monde. Non que l’on doive l’endurer, mais comme elle est là, il faut la comprendre et la dépasser. C’est là une des qualités d’un esprit religieux - dans le sens où nous utilisons ce mot - qui est incapable de souffrir. Car il a dépassé cela. Ce qui ne signifie pas pour autant qu’il soit devenu insensible. Au contraire, c’est un esprit passionné.

A : Pendant nos entretiens, j’ai beaucoup pensé à la question du langage. D’une part, nous disons qu’un esprit tel que celui que vous avez décrit, est présent à la souffrance. Il ne fait rien pour la repousser et, pourtant, il est capable de la contenir d’une certaine façon, non pas, en la plaçant dans un vase ou un tonneau pour la contenir dans ce sens-là. D’autre part, le mot souffrir suppose la notion de supporter qui se rapproche de comprendre. Pendant nos conversations, j’ai été conscient de ce que l’usage habituel que nous faisons du langage nous prive en réalité de la merveilleuse perception de la substance même des mots. Prenons le mot « religion » dont nous parlions tout à l’heure. Les savants sont en désaccord sur son origine. Certains avancent qu’il signifie « relier ».

K : Lier, du latin ligarer.

A : Les pères de l’église, le disaient, et d’autres le nient, disant que c’est la volonté divine, la splendeur, que la pensée ne peut tarir. Il me semble que « relier » comporte un autre sens non négatif, à savoir que si l’on pratique cet acte d’attention, aucun lien, ni aucune corde ne nous attache. On est à la fois là-bas et ici.

K : A nouveau M. soyons clairs. Quand nous utilisons le mot « attention ». Il faut distinguer entre concentration et attention. La concentration exclue. Je me concentre, c’est-à-dire, je focalise toute ma pensée sur un certain point, ce qui par conséquent exclue, en érigeant une barrière de sorte que toute la concentration se focalise sur cela. Tandis que l’attention diffère totalement de la concentration. Dans l’attention, il n’y a ni exclusion, ni résistance, ni effort. Par conséquent aucune frontière, aucune limite.

A : Que diriez-vous du mot réceptif, à ce sujet ?

K : Là encore, qui doit recevoir ?

A : Nous avons déjà créé une division avec ce mot.

K : Je pense que « attention » est vraiment un très bon mot, car non seulement il comprend la concentration, non seulement il voit la dualité de la réception, - celui qui reçoit et la chose reçue - mais aussi il voit la nature de la dualité et le conflit des opposés ; et l’attention signifie que le cerveau, mais aussi l’esprit, le cœur, les nerfs, l’entité globale, l’esprit humain dans sa totalité consacre toute son énergie à percevoir. Je pense que tel est le sens de ce mot, tout au moins pour moi, être attentif, prêter attention. Pas se concentrer mais prêter attention. Ce qui signifie écouter, voir, consacrer son cœur, son esprit, tout son être à cette attention, sinon l’attention n’est pas possible. Si je pense à autre chose, si j’écoute ma propre voix, je ne puis prêter attention.

A : Les écritures utilisent le mot attendre. Métaphoriquement. Il est intéressant de constater qu’on se sert du mot « intendant », pour désigner un administrateur. J’essaie de trouver en cela une corrélation avec attendre, patienter.

K : Je pense qu’ici encore attendre se réfère à « quelqu’un qui attend quelque chose ». D’où à nouveau une dualité. Et quand vous attendez, vous anticipez quelque chose. Encore une dualité. Celle de celui qui attend de recevoir. Si nous pouvons pour un instant nous en tenir au mot attention, nous devrions alors nous informer sur la qualité d’un esprit tellement attentif qu’il a compris, qu’il vit, qu’il agit dans la relation avec un comportement responsable et psychologiquement sans peur - nous en avons parlé -. Par conséquent, il comprend le mouvement du plaisir. Dès lors, nous en venons à ceci : qu’est-ce qu’un tel esprit ? Je pense qu’il vaudrait la peine de discuter ici, de la nature de la blessure.

A : De la blessure ? Oui.

K : Pourquoi les êtres humains sont-ils blessés ? Tout le monde l’est !

A : Physiquement et psychologiquement ?

K : Surtout psychologiquement.

A : Tout spécialement.

K : Physiquement, on peut supporter une douleur et dire : « je ne la laisse pas agir sur ma pensée, je ne vais pas la laisser corrompre la qualité psychologique de mon esprit ». L’esprit peut veiller à cela. Mais les blessures psychologiques sont bien plus importantes et difficiles à cerner et comprendre. Je pense que c’est nécessaire, car un esprit blessé n’est pas un esprit innocent. Le mot « innocent » vient de « innocere ». Ne pas blesser. Un esprit qui ne peut pas être blessé. Quelle beauté !

A : En effet, c’est un mot merveilleux. On s’en sert généralement pour indiquer un manque. Et voilà son sens à nouveau renversé.

K : Les chrétiens en ont fait une chose tellement absurde.

A : Oui, je comprends.

K : Il me semble donc qu’en discutant de religion nous devrions approfondir avec soin la nature de la blessure, car l’esprit qui n’est pas blessé est un esprit innocent. Et cette qualité d’innocence est nécessaire pour être totalement attentifs.

A : Si je vous ai bien suivi, peut-être faudrait-il dire qu’un homme se sent blessé dans la mesure où sa pensée s’est emparée de cette blessure.

K : Voyons M. c’est bien plus profond. Dès l’enfance, les parents comparent un enfant à un autre.

A : C’est là que la pensée surgit.

K : La voilà. Quand vous comparez, vous blessez, c’est bien ce que l’on fait.

A : Oh ! oui. Bien sûr.

K : Alors, est-il possible d’éduquer un enfant sans comparaison, sans imitation ? Et par conséquent éviter toute blessure de ce fait. On est blessé, car on s’est construit une image de soi. Cette image amène une forme de résistance, un mur entre vous et moi et quand vous touchez ce mur sur un point sensible, je suis blessé. Il s’agit donc de ne pas comparer dans l’éducation, de ne pas avoir une image de soi. C’est une des choses les plus importantes dans la vie, ne pas avoir une image de soi. Si vous en avez une, vous serez inévitablement blessé. Supposons que l’on ait de soi l’image de quelqu’un de très bon, ou qui doit réussir ? ou avoir de grands talents, dons, - vous connaissez ces images -, vous allez inévitablement y planter une flèche. Accidents et incidents vont inévitablement se produire et briser cette image, et l’on est blessé.

A : Cela ne soulève-t-il pas la question du nom ?

K : Oh, oui.

A : L’usage du nom.

K : Oui, le nom, la forme.

A : L’enfant reçoit un nom auquel il s’identifie.

K : Oui. L’enfant peut s’identifier mais sans image seulement avec un nom : Monsieur Brun. Sans plus. Mais dès qu’il construit l’image selon laquelle monsieur Brun est socialement, moralement supérieur ou inférieur, qu’il descend d’une famille très ancienne, qu’il appartient à une classe élevée, à l’aristocratie, dès l’instant où cela commence, et si s’est encouragé et soutenu par la pensée, le snobisme etc. Alors, la blessure devient inévitable.

A : D’après ce que vous dites, je suppose que l’on commet une erreur fondamentale en s’identifiant à son nom.

K : Oui. L’identification au nom, au corps, à l’idée que l’on est socialement différent, que ses parents, grands-parents étaient des seigneurs, ceci et cela. Vous connaissez tout ce snobisme qui existe en Angleterre, ou sous une autre forme dans ce pays-ci.

A : On dit qu’il faut préserver le nom.

K : En Inde, c’est toute l’histoire du brahmane, du non brahmane etc. ainsi, nous nous sommes construit une image de soi à travers l’éducation, la tradition, la propagande.

A : Y a-t-il ici un rapport en terme de religion avec le fait de ne pas prononcer le nom de Dieu, par exemple ? dans la tradition hébraïque.

K : Le mot n’est pas la chose. Vous pouvez le prononcer ou non. Si vous savez que le mot n’est jamais la chose, la description, jamais la chose décrite, alors peu importe.

A : Une des raisons pour lesquelles je me suis profondément intéressé à l’étude de la racine des mots est due au fait que souvent ils indiquent quelque chose de très concret. Il s’agit soit d’une chose, d’un geste le plus souvent un acte.

K : Tout à fait.

A : Un acte. Quand je disais la phrase « penser à la pensée », j’aurais dû être plus attentif au choix des mots et dire plutôt « ruminer sur l’image », ce qui aurait été bien plus approprié. Non ?

K : Oui.

A : Oui, oui.

K : Alors, un enfant peut-il être éduqué de façon à ne jamais être blessé ? J’ai entendu un professeur dire qu’un enfant doit être blessé afin d’apprendre à vivre dans le monde. Quand j’ai demandé s’il voulait que son enfant soit blessé, il est resté silencieux. Il ne faisait que parler théoriquement. De nos jours, malheureusement, l’éducation, la structure et la nature de la société dans laquelle nous vivons, nous amène à nous construire des images de soi qui seront blessées. Alors, est-il possible de ne pas créer la moindre image ? Je ne sais pas si je suis clair ?

A : Vous l’êtes.

K : Ainsi, supposons que j’ai une image de moi. Je n’en ai pas, heureusement. Si j’ai une image, est-il possible de la balayer, de la comprendre et par conséquent de la dissoudre pour ne plus jamais en créer une nouvelle ? N’est-ce pas ? Vivant dans une société y étant éduqué, j’ai inévitablement construit cette image. Alors, cette image ne peut-elle être balayée ?

A. : Disparaîtrait-elle par cet acte d’attention totale ?

K : J’y viens graduellement. Elle disparaîtrait complètement. Mais je dois comprendre comment cette image est née. Je ne peux me contenter de dire « je la balaie ».

A : Oui. Il faut ...

K : ... user de l’attention pour la balayer. Cela ne marche pas ainsi. C’est en comprenant l’image, les blessures, l’éducation que nous avons reçue de la famille, de la société, c’est par la compréhension de cela que vient l’attention, pas en commençant par l’attention, puis en balayant l’image. On ne peut être attentif en étant blessé. Comment puis-je prêter attention si je suis blessé ? Cette blessure va m’écarter, consciemment ou inconsciemment, de cette attention totale.

A : Ce qui est stupéfiant, si je vous comprends bien, c’est que même dans l’étude de l’histoire dysfonctionnelle, si je prête une attention entière à cela, il y aura relation non-temporelle dans l’acte d’attention et la guérison s’opère. Pendant que je suis attentif, la chose s’en va.

K : En effet.

A : Nous devons rester attentif à la chose.

K : Oui, exactement. Ceci implique deux questions. Les blessures peuvent-elles être guéries sans laisser de cicatrice ? Et des blessures futures peuvent-elles être évitées totalement, sans la moindre résistance ? Vous suivez ? Il y a là deux problèmes. Ceux-ci ne peuvent être compris et résolus que si je prête attention à la compréhension de mes blessures. Et en le regardant, sans les traduire, ni souhaiter les balayer, juste les regarder, comme on l’a fait pour la perception. Il s’agit simplement de regarder mes blessures. Les blessures reçues : les insultes, la négligence, la parole désinvolte, le geste, tout ceci blesse. Et les paroles dont on se sert, particulièrement dans ce pays.

A : Oh ! Oui. Il semble y avoir un rapport entre ce que vous dites et une des significations du mot « salut ».

K : « Salvare ». Sauver.

A : Sauver. Rendre l’intégrité.

K : Rendre l’intégrité. Comment être intégre si l’on est blessé ?

A : Impossible.

K : C’est pourquoi il est terriblement important de comprendre cette question.

A : Oui. En effet. Mais je pense à un enfant qui vient à l’école avec un chargement de blessures.

K : Je sais.

A : Il ne s’agit pas d’un bébé au berceau.

K : Il y a déjà des blessures.

A : Déjà blessé et il blesse à son tour. Cela se multiplie sans fin.

K : Bien sûr. Cette blessure le rend violent, il en a peur et par conséquent il se renferme. Cette blessure l’amènera à des actions névrotiques. Cette blessure l’amènera à accepter tout ce qui peut lui apporter la sécurité, Dieu, son idée de Dieu est un Dieu qui ne blessera jamais.

A : A ce sujet, une distinction est parfois faite entre les animaux et nous par exemple un animal sérieusement blessé aura envers chacun une attitude se manifestant en terme d’urgence et d’attaque.

K : D’attaque.

A : Mais au bout d’un certain temps, peut-être trois ou quatre ans si l’animal reçoit de l’amour...

K : Voyez-vous M., vous avez dit « amour ». C’est une chose que nous n’avons pas. Des parents n’ont pas d’amour pour leurs enfants. Ils en parlent peut être. Mais dès l’instant où ils comparent le plus jeune à l’aîné, ils ont blessé l’enfant. « Votre père était si malin et toi tu es un garçon si stupide », c’est là que vous avez commencé. Les notes que l’on donne à l’école, se sont des blessures. Ce ne sont pas des notes mais des blessures délibérées. Cela est emmagasiné et de là vient la violence, toutes sortes d’agressions, vous savez tout ce qui se passe. Donc un esprit ne peut être rendu à la totalité ou être total, si tout cela n’est pas compris très profondément.

A : Ce que je voulais dire à propos de l’animal, c’est que dans la mesure où des dégâts n’ont pas été occasionnés au cerveau, ou quelque chose chose, s’il lui est prodigué de l’amour, il aimera un jour à son tour. Bien entendu, chez un être humain, l’amour ne peut être imposé. Il ne s’agit pas de forcer un animal à aimer, mais l’innocence de celui-ci fera qu’un jour il répondra simplement, il acceptera. Au bout d’un certain temps il répondra simplement, il acceptera. Mais l’être humain agit autrement qu’un animal. Il aimera un jour à son tour.

K : Non. L’être humain est blessé et blesse sans cesse.

A : Mais l’être humain agit d’une façon que nous n’attendrions pas d’un animal.

K : Non. L’être humain est blessé et blesse sans cesse.

A : Exactement, et pendant qu’il rumine sur sa blessure, il est susceptible de mal interpréter l’acte de générosité et d’amour dirigé vers lui, nous voilà face à quelque chose d’effrayant : quand l’enfant arrive à l’école à sept ans...

K : ... il est déjà entamé, torturé. C’est bien là la tragédie. C’est ce que je veux dire.

A : Oui, je sais. Et quand vous posez la question de savoir s’il existe une façon d’éduquer l’enfant afin ...

K : ... afin qu’il ne soit jamais blessé, cela fait partie de l’éducation, de la culture. La civilisation blesse. Regardez M., cela se voit partout dans le monde, cette constante comparaison, cette constante imitation, cette façon constante de dire « tu es comme cela, je dois être comme toi, comme Krishna, comme Bouddha, comme Jésus » - vous suivez ? c’est une blessure. Les religions ont blessé les gens.

A : L’enfant naît d’un parent blessé, il est envoyé à l’école où il est enseigné par un professeur blessé. Vous demandez s’il existe une façon d’éduquer cet enfant de sorte qu’il puisse récupérer.

K : Je dis que c’est possible.

A : Oui.

K : Quand le professeur, l’éducateur se rend compte qu’il est blessé et que l’enfant l’est aussi, quand il est conscient de sa blessure et de celle de l’enfant, alors leur relation change. Dès lors dans l’acte même d’enseigner les mathématiques ou autre chose, non seulement il se libère de sa blessure, mais il aide aussi l’enfant à en faire de même. Après tout, c’est cela l’éducation : voir que moi, le professeur, je suis blessé et ai traversé des angoisses de blessure et que je veux aider cet enfant à ne pas être blessé, alors qu’il est venu à l’école déjà blessé. Donc je dis « très bien nous voilà tous deux blessés mon ami, voyons si nous pouvons nous entraider à balayer cela ». C’est là un acte d’amour.

A : En comparant l’organisme humain à celui de l’animal je reviens à la question de savoir si cette relation avec un autre être humain, amène la guérison.

K : Oui, dans la mesure où cette relation existe. Et la relation n’existe que s’il n’y a aucune image entre vous et moi.

A : Disons, qu’il existe un professeur qui prend ce problème à bras le corps, chez lui-même, qu’il a, comme vous avez dit, pénètré la question de plus en plus profondément, pour en venir au point qu’il n’est plus sujet aux blessures. Il rencontre l’enfant, le jeune étudiant ou même un étudiant de son âge - car l’éducation pour adultes existe - qui eux sont pris dans leurs blessures.

K : Transmettra-t-il sa blessure ?

A : Non, du fait qu’il est sujet aux blessures, ne va t-il pas mal interpréter l’activité de celui qui ne l’est pas ?

K : Très rares sont les personnes qui ne sont pas sujettes aux blessures. Bien des choses me sont arrivées, mais je n’ai jamais été blessé. Je dis cela en toute humilité dans le vrai sens du terme. J’ignore ce qu’être blessé veut dire. Les choses me sont arrivées, des gens ont agi avec moi de diverses façons : ils m’ont loué, flatté, bousculé, tout ce que vous voudrez. C’est possible. En tant que professeur et éducateur, il est de ma responsabilité de veiller à ce que l’enfant ne soit jamais blessé, ceci est bien plus important que d’enseigner quelques malheureuses matières.

A : Je pense saisir ce dont vous parlez. Je ne pourrais certainement pas affirmer n’avoir jamais été blessé. Comme j’ai un enfant je m’efforce d’agir de cette façon, malgré les difficultés. Je me souviens qu’en discutant d’une situation conflictuelle en Faculté, un collègue m’a dit avec une certaine irritation :

![]() « l’ennui avec vous est que vous ne pouvez haïr ».

« l’ennui avec vous est que vous ne pouvez haïr ».

Il considérait cela comme du désordre, parce que cela l’empêchait de se braquer contre un ennemi susceptible d’accaparer toute son attention.

K : Ce qui est sain est considéré comme malsain.

A : Oui. Ma réponse fut :

![]() « c’est juste, alors autant accepter la situation telle qu’elle est sans rien faire d’autre ».

« c’est juste, alors autant accepter la situation telle qu’elle est sans rien faire d’autre ».

K : Tout à fait.

A : Mais cela n’a pas facilité notre relation.

K : La question est donc : un professeur, un éducateur peut-il observer ses blessures, en devenir conscient dans ses rapports avec l’étudiant amenant par là la résolution des blessures de l’un et de l’autre ? C’est un des problèmes. C’est possible, dans la mesure ou le professeur est réellement cultivé au sens profond de ce terme. La question suivante est : l’esprit est-il capable de ne pas être à nouveau blessé, sachant qu’il l’a été ? Vous savez ? Ne pas ajouter de blessures. N’est-ce pas ?

A : Oui.

K : J’ai donc deux problèmes, d’une part, le fait d’être blessé - c’est le passé - et ne jamais être blessé à nouveau. Sans m’entourer d’un mur de résistance, ou me retirer, entrer au monastère ou devenir un drogué ou autre stupidité de la sorte, mais ne plus être blessé. Est-ce possible ? Vous voyez les deux questions ? Alors, qu’est ce que la blessure ? Qu’elle est la chose qui est blessée ? Vous suivez ?

A : Oui

K : Nous avons dit que les blessures physiques et psychologiques diffèrent. Nous traitons ici de la blessure psychologique. Quelle est la chose qui est blessée ? Le psychisme ? L’image que j’ai de moi ?

A : J’ai investi dans cette image.

K : Oui j’ai investi en moi-même.

A : Oui. Je me suis séparé de moi-même.

K : En moi-même. Pourquoi devrais-je investir en moi-même ? Qu’est-ce que moi-même, vous suivez ? ...

A : Oui ...

K : ... dans lequel je dois investir quelque chose ? Qu’est-ce que moi-même ? Tous les mots, noms, qualités, l’éducation, le compte en banque, le mobilier, la maison, les blessures – tout cela est moi -.

A : Quand je me demande ce qu’est « moi », je dois faire appel à tout cela.

K : Il n’y a pas d’autre manière.

A : Mais je n’y arrive pas. Je me loue alors d’être si merveilleux, comme pour m’échapper.

... RIRES ...

K : Tout à fait.

A : Je vois ce que vous voulez dire. Je pensais à ce que nous disions plutôt quand nous nous demandions si le professeur peut nouer avec l’étudiant une relation d’une qualité telle qu’un acte de guérison en découlerait.

K : Si j’étais professeur, c’est par là que je commencerais, pas par enseigner une matière. Je dirais « vous êtes blessé, moi aussi, nous sommes tous deux blessés ». J’indiquerais les conséquences de la blessure : elle tue et détruit les gens, il en découle violence et brutalité, et le fait que je veux blesser les gens. Tout cela entre en jeux. J’y consacrerais dix minutes par jour en présentant la chose de différentes façons, jusqu’à ce que nous voyions bien. En tant qu’éducateur, j’userais du mot juste et l’étudiant aussi, il n’y aurait ni geste, ni irritation, nous sommes tous deux concernés. Mais nous ne le faisons pas. Quand nous entrons en classe, nous prenons un livre et c’est parti. Si j’étais éducateur j’établirais ce type de relation, que ce soit avec des jeunes ou des plus âgés. C’est là mon devoir, mon métier, ma fonction, et non de me limiter à transmettre des informations.

A : Oui, c’est vraiment très profond. Je pense qu’une des raisons pour lesquelles ce que vous avez dit est si difficile pour un éducateur nourri par le monde académique…

K : Oui, car nous sommes si vains !

A : Exactement. Nous ne voulons pas seulement entendre que cette transformation est possible, mais nous voulons qu’elle soit démontrable, c’est-à-dire prévisible et certaine.

K : Certaine, oui.

A : Et nous voilà de retour à la case départ.

K : De retour dans toute cette confusion.

A : La prochaine fois, pourrions-nous aborder ce qui relie ceci à l’amour ?

K : Oui. Nous le ferons.

A : J’en serais très heureux et il me semble ...

K : ... Tout cela se tient.

A : Allons ensemble à cette rencontre .

Texte anglais :

J. Krishnamurti, Eleventh Conversation with Dr Allan W. Anderson in San Diego California, 25 February 1974

J. Krishnamurti was born in South India and educated in England. For the past 40 years he has been speaking in the United States, Europe, India, Australia and other parts of the world. From the outset of his life’s work he repudiated all connections with organised religions and ideologies and said that his only concern was to set man absolutely unconditionally free. He is the author of many books, among them The Awakening of Intelligence, The Urgency of Change, Freedom From the Known, and The Flight of the Eagle.

This is one of a series of dialogues between Krishnamurti and Dr. Allan W. Anderson, who is professor of religious studies at San Diego State University where he teaches Indian and Chinese scriptures and the oracular tradition. Dr. Anderson, a published poet, received his degree from Columbia University and the Union Theological Seminary. He has been honoured with the distinguished teaching award from the California State University.

THE NATURE OF HURT

A : Mr Krishnamurti, during our conversations one thing has emerged for me with, I’d say, an arresting force. That is, on the one hand we have been talking about thought and knowledge in terms of a dysfunctional relationship to it, but never once have you said that we should get rid of thought, and you have never said that knowledge, as such, in itself, has something profoundly the matter with it. Therefore the relationship between intelligence and thought arises, and the question of what seems to be that which maintains a creative relationship between intelligence and thought - perhaps some primordial activity which abides. And in thinking on this I wondered whether you would agree that perhaps in the history of human existence the concept of god has been generated out of a relationship to this abiding activity, which concept has been very badly abused. And it raises the whole question of the phenomenon of religion itself. I wondered if we might discuss that today ?

K : Yes, sir. You know, a word like religion, love, or god, has almost lost all its meaning. They have abused these words so enormously, and religion has become a vast superstition, a great propaganda, incredible beliefs and superstitions, worship of images made by the hand or by the mind. So when we talk about religion I would like, if I may, to be quite clear that we are both of us using the word ’religion’ in the real sense of that word, not either in the Christian, or the Hindu, or the Muslim, or the Buddhist, or all the stupid things that are going on in this country in the name of religion.

I think the word ’religion’ means gathering together all energy, at all levels, physical, moral, spiritual, at all levels, gathering all this energy which will bring about a great attention. And in that attention there is no frontier, and then from there move. To me that is the meaning of that word : the gathering of total energy to understand what thought cannot possibly capture. Thought is never new, never free, and therefore it is always conditioned and fragmentary, and so on, which we discussed. So religion is not a thing put together by thought, or by fear, or by the pursuit of satisfaction and pleasure, but something totally beyond all this, which isn’t romanticism, speculative belief, or sentimentality. And I think if we could keep to that, to the meaning of that word, putting aside all the superstitious nonsense that is going on in the world in the name of religion, which has become really quite a circus, however beautiful it is. Then I think we could from there start, if you will. If you agree to the meaning of that word.

A : Yes. I have been thinking as you have been speaking that in the biblical tradition there are actual statements from the prophets which seem to point to what you are saying. Such things come to mind as Isaiah’s, taking the part of the divine, when he says, ’My thoughts are not your thoughts, my ways are not your ways, as high as the heavens are above the earth so are my thoughts and your thoughts, so stop thinking about me in that sense’.

K : Yes, quite.

A : And don’t try to find a means to me that you have contrived since my ways are higher than your ways. And then I was thinking while you were speaking concerning this act of attention, this gathering together of all energies of the whole man ; the very simple, ’Be still and know that I am God’. Be still. It’s amazing when one thinks of the history of religion, how little attention has been paid to that as compared with ritual.

K : But I think when we lost touch with nature, with the universe, with the clouds, lakes, birds, when we lost touch with all that, then the priests came in. Then all the superstition, fears, exploitation, all that began. The priest became the mediator between the human and the so-called divine. And I believe, if you have read the Rig Veda - I was told about it because I don’t read all this - that there, in the first Veda there is no mention of God at all. There is only this worship of something immense, expressed in nature, in the earth, in the clouds, in the trees, in the beauty of vision. But that being, very, very simple, the priests said, that is too simple.

A : (laughs) Let’s mix it up.

K : Let’s mix it up, let’s confuse it a little bit. And then it began. I believe this is traceable from the ancient Vedas to the present time, where the priest became the interpreter, the mediator, the explainer, the exploiter ; the man who said, this is right, this is wrong, you must believe this or you will go to perdition, and so on and so on and so on. He generated fear, not the adoration of beauty, not the adoration of life lived totally wholly without conflict, but something placed outside there, beyond and above what he considered to be God and made propaganda for that.

So I feel if we could from the beginning use the word ’religion’ in the simplest way. That is, the gathering of all energy so that there is total attention, and in that quality of attention the immeasurable comes into being. Because as we said the other day, the measurable is the mechanical. Which the west has cultivated, made marvellous, technologically, physically - medicine, science, biology and so on and so on, which has made the world so superficial, mechanical, worldly, materialistic. And that is spreading all over the world. And in reaction to that - this materialistic attitude - there are all these superstitious, nonsensical, unreasoned religions that are going on. I don’t know if you saw the other day the absurdity of these gurus coming from India and teaching the west how to meditate, how to hold breath, they say, ’I am god, worship me’ and falling at their feet, you know - it has become so absurd, and childish, so utterly immature. All that indicates the degradation of the word ’religion’, and the human mind that can accept this kind of circus and idiocy.

A : Yes. I was thinking of a remark of Sri Aurobindo’s in a study that he made on the Veda, where he traced its decline in this sentence. He said it issues as language from sages, then it falls to the priests, and then after the priests it falls to the scholars or the academicians. But in that study there was no statement that I found as to how it ever fell to the priests. And I was wondering whether...

K : I think it is fairly simple, sir.

A : Yes, please.

K : I think it is fairly simple, sir, how the priests got hold of the whole business. Because man is so concerned with his own petty little affairs, petty little desires, and ambitions, superficiality, he wants something, a little more : he wants a little more romantic, a little more sentimental, more something other than the daily beastly routine of living. So he looks somewhere and the priests say, ’Hey, come over here, I’ve got the goods’. I think it is very simple how the priests have come in. You see it in India, you see it in the west. You see it everywhere where man begins to be concerned with daily living, the daily operation of bread and butter, house and all the rest of it, he demands something more than that. He says, after all I’ll die but there must be something more.

A : So fundamentally it’s a matter of securing for himself some...

K : ...heavenly grace.

A : ...some heavenly grace that will preserve him against falling into this mournful round of coming to be and passing away. Thinking of the past, on the one hand, anticipating the future on the other, you’re saying he falls out of the present now.

K : Yes, that’s right.

A : I understand.

K : So, if we could keep to that meaning of that word ’religion’ then from there the question arises : can the mind be so attentive in the total sense that the unnameable comes into being ? You see, personally I have never read any of these things, Vedas, Bhagavad-Gita, Upanishads, the Bible, all the rest of it, or any philosophy. But I questioned everything.

A : Yes.

K : Not questioned only, but observe. And I - one sees the absolute necessity of a mind that is completely quiet. Because it’s only out of quietness you perceive what is happening. If I am chattering I won’t listen to you. If my mind is constantly rattling away, to what you are saying I won’t pay attention. To pay attention means to be quiet.

A : There have been some priests, apparently, who usually ended up in a great deal of trouble for it, there have been some priests who had, it seems, a grasp of this. I was thinking of Meister Eckhardt’s remark that whoever is able to read the book of nature doesn’t need any scriptures at all.

K : At all, that’s just it, sir.

A : Of course, he ended up in very great trouble. Yes, he had a bad time toward the end of his life, and after he died the church denounced him.

K : Of course, of course. Organised belief as church, and all the rest of it, is too obvious. It isn’t subtle, it hasn’t got the quality of real depth and real spirituality. You know what it is.

A : Yes, I do.

K : So I’m asking : what is the quality of a mind, and therefore heart and brain, what is the quality of a mind that can perceive something beyond the measurement of thought ? What is the quality of a mind ? Because that quality is the religious mind. That quality of a mind that is capable, that has this feeling of being sacred in itself, and therefore is capable of seeing something immeasurably sacred.

A : The word ’devotion’ seems to imply this when it is grasped in its proper sense. To use your earlier phrase, gathering together toward a one pointed, attentive...

K : Would you say attention is one pointed ?

A : No, I didn’t mean to imply focus when I said one pointed.

K : Yes, that’s what I wondered.

A : I meant rather, integrated into itself as utterly quiet and unconcerned about taking thought for what is ahead, or what is behind. Simply being there. The word ’there’ isn’t good either because it suggests that there is a ’where’ and ’here’, and all the rest of it. It is very difficult to find, it seems to me, language to do justice to what you are saying, precisely because when we speak utterance is in time and it is progressive, it has a quality, doesn’t it, more like music than we see in graphic art. You can stand before a picture, whereas to hear music and grasp its theme you virtually have to wait until you get to the end and gather it all up.

K : Quite.

A : And with language you have the same difficulty.

K : No, I think, sir, don’t you, when we are enquiring into this Problem : what is the nature and the structure of a mind, and therefore the quality of a mind, that is not only sacred and holy in itself, but is capable of seeing something immense ? As we were talking the other day about suffering, personal and the sorrow of the world, it isn’t that we must suffer, suffering is there. Every human being has a dreadful time with it. And there is the suffering of the world. And it isn’t that one must go through it, but as it is there one must understand it and go beyond it. And that’s one of the qualities of a religious mind, in the sense we are using that word, that is incapable of suffering. It has gone beyond it. Which doesn’t mean that it becomes callous. On the contrary it is a passionate mind.

A : One of the things that I have thought much about during our conversations is language itself. On the one hand we say such a mind as you have been describing, is one that is present to suffering. It does nothing to push it away, on the one hand ; and yet it is somehow able to contain it, not put it in a vase, or barrel, and contain it in that sense, and yet the very word itself, to suffer, means to under-carry. And it seems close to understand. Over and over again in our conversations I have been thinking about the customary way in which we use language as a use that deprives us of really seeing the glory of what the word points to itself, in itself. I was thinking about the word religion when we were speaking earlier. Scholars differ as to where that came from : on the one hand some say that it means to bind...

K : Bind - ligare.

A : ...the church fathers spoke about that. And then others say, no, no, it means the numinous or the splendour that cannot be exhausted by thought. It seems to me that, wouldn’t you say, that there is another sense to ’bind’ that is not a negative one, in the sense that if one is making this act of attention, one isn’t bound as with cords of ropes. But one is there, or here.

K : Sir, now again let’s be clear. When we use the word attention there is a difference between concentration and attention. Concentration is exclusion. I concentrate. That is, bring all my thinking to a certain point, and therefore it is excluding, building a barrier so that it can focus its whole concentration on that. Whereas attention is something entirely different from concentration. In that there is no exclusion. In that there is no resistance. In that there is no effort. And therefore no frontier, no limits.

A : How would you feel about the word ’receptive’, in this respect ?

K : Again, who is it that is to receive ?

A : Already we have made a division.

K : A division.

A : With that word.

K : Yes. I think the word ’attention’ is really a very good word. Because it not only understands concentration, not only sees the duality of reception, the receiver and the received, and also it sees the nature of duality and the conflict of the opposites ; and attention means not only the brain giving its energy, but also the mind, the heart, the nerves, the total entity, the total human mind giving all its energy to perceive. I think that is the meaning of that word for me at least, to be attentive, attend. Not concentrate, attend. That means listen, see, give your heart to it, give your mind to it, give your whole being to attend, otherwise you can’t attend. If I am thinking about something else I can’t attend. If I am hearing my own voice, I can’t attend.

A : There is a metaphorical use of the word ’waiting’ in scripture. It’s interesting that in English too we use the word attendant in terms of one who waits on. I’m trying to penetrate the notion of waiting, and patience in relation to this.

K : I think, sir, waiting again means one who is waiting for something. Again there is a duality in that. And when you wait you are expecting. Again a duality. One who is waiting, about to receive. So if we could for the moment hold ourselves to that word, ’attention’, then we should enquire what is the quality of a mind that is so attentive that it has understood, lives, acts, in relationship and responsibility as behaviour, and has no fear psychologically in that, we talked about, and therefore understands the movement of pleasure. Then we come to the point, what is such a mind ? I think it would be worthwhile if we could discuss the nature of hurt.

A : Of hurt ? Yes.

K : Why human beings are hurt. All people are hurt.

A : You mean both the physical and the psychological ?

K : Psychological especially.

A : Especially the psychological one, yes.

K : Physically we can tolerate it. We can bear up with a pain and say I won’t let it interfere with my thinking. I won’t let it corrode my psychological quality of mind. The mind can watch over that. But the psychological hurts are much more important and difficult to grapple with and understand. I think it is necessary because a mind that is hurt is not an innocent mind. The very word ’innocent’ comes from ’innocere’, not to hurt. A mind that is incapable of being hurt. And there is a great beauty in that.

A : Yes, there is. It’s a marvellous word. We have usually used it to indicate a lack of something.

K : I know.

A : Yes, and there it’s turned upside down again.

K : And the Christians have made such an absurd thing of it.

A : Yes, I understand that.

K : So I think we ought to, in discussing religion, we ought to enquire very, very deeply into the nature of hurt, because a mind that is not hurt is an innocent mind. And you need this quality of innocency to be so totally attentive.

A : If I have been following you correctly I think may be you would say, wouldn’t you, that one becomes hurt when he starts thinking about thinking that he is hurt.

K : Look sir, it’s much deeper than that, isn’t’ it ? From childhood the parents compare the child with another child.

A : That’s when that thought arises.

K : There it is. When you compare you are hurting.

A : Yes.

K : No, but we do it.

A : Oh yes, of course we do it.

K : Therefore is it possible to educate a child without comparison, without imitation ? And therefore never get hurt in that way. And one is hurt because one has built an image about oneself. The image which one has built about oneself is a form of resistance, a wall between you and me. And when you touch that wall at its tender point I get hurt. So not to compare in education, not to have an image about oneself. That’s one of the most important things in life, not to have an image about oneself. If you have you are inevitably going to be hurt. Suppose one has an image that one is very good, or that one should be a great success, or that one has great capacities, gifts, you know the images that one builds, inevitably you are going to come and prick it. Inevitably accidents and incidents happen that’s going to break that, and one gets hurt.

A : Doesn’t this raise the question of name ?

K : Oh, yes.

A : The use of name.

K : Name, form.

A : The child is given a name, the child identifies himself with the name.

K : Yes, the child can identify itself but without the image, just a name : Brown, Mr Brown. There is nothing to it ! But the moment he builds an image that Mr Brown is socially, morally different, superior, or inferior, ancient or comes from a very old family, belongs to a certain higher class, aristocracy. The moment that begins, and when that is encouraged and sustained by thought, snobbism, you know the whole of it, how it is, then you are inevitably going to be hurt.

A : What you are saying, I take it, is that there is a radical confusion here involved in the imagining oneself to be his name.

K : Yes. Identification with the name, with the body, with the idea that you are socially different, that your parents, your grandparents were lords, or this or that. You know the whole snobbism of England, and all that, and the different kind of snobbism in this country.

A : We speak in language of preserving our name.

K : Yes. And in India it is the Brahmin, the non Brahmin, the whole business of that. So through education, through tradition, through propaganda we have built an image about ourselves.

A : Is there a relation here in terms of religion, would you say, to the refusal, for instance in the Hebraic tradition, to pronounce the name of God.

K : The word is not the thing anyhow. So you can pronounce it or not pronounce it. If you know the word is never the thing, the description is never the described, then it doesn’t matter.

A : No. One of the reasons I’ve always been over the years deeply drawn to the study of the roots of words is simply because for the most part they point to something very concrete.

K : Very.

A : It’s either a thing or it’s a gesture, more often than not it’s some act.

K : Quite, quite.

A : Some act. When I use the phrase, thinking about thinking, before, I should have been more careful of my words and referred to mulling over the image, which would have been a much better way to put it, wouldn’t it ?

K : Yes, yes. So can a child be educated never to get hurt ? And I have heard professors, scholars, say, a child must be hurt in order to live in the world. And when I asked him, ’Do you want your child to be hurt ?’ he kept absolutely quiet. It was just talking theoretically. Now unfortunately, through education, through social structure and the nature of our society in which we live, we have been hurt, we have images about ourselves which are going to be hurt, and is it possible not to create images at all ? I don’t know if I am making myself clear.

A : You are.

K : That is, suppose I have an image about myself - which I haven’t fortunately - if I have an image, is it possible to wipe it away, to understand it and therefore dissolve it, and never to create a new image about myself ? You understand ? Living in a society, being educated, I have built an image, inevitably. Now can that image be wiped away ?

A : Wouldn’t it disappear with this complete act of attention ?

K : That’s what I’m coming to gradually. It would totally disappear. But I must understand how this image is born. I can’t just say, ’Well, I’ll wipe it out’.

A : Yes, we have to...

K : Use attention as a means of wiping it out - it doesn’t work that way. In understanding the image, in understanding the hurts, in understanding the education in which one has been brought up, in the family, the society, all that, in the understanding of that, out of that understanding comes attention ; not the attention first and then wipe it out. You can’t attend if you’re hurt. If I am hurt how can I attend ? Because that hurt is going to keep me, consciously or unconsciously, from this total attention.

A : The amazing thing, if I’m understanding you correctly, is that even in the study of the dysfunctional history, provided I bring total attention to that, there’s going to be a non-temporal relationship between the act of attention and the healing that takes place.

K : Absolutely, that’s right.

A : While I am attending the thing is leaving.

K : The thing is leaving, yes, that’s it.

A : We’ve got ’thinging’ along here throughout. Yes, exactly.

K : So, there are two questions involved : can the hurts be healed so that not a mark is left ; and can future hurts be prevented completely, without any resistance. You follow ? Those are two problems. And they can be understood only and resolved when I give attention to the understanding of my hurts. When I look at it, not translate it, not wish to wipe them away, just to look at it - as we went into that question of perception. Just to see my hurts. The hurts I have received : the insults, the negligence, the casual word, the gesture - all those hurt. And the language one uses, specially in this country.

A : Oh yes, yes. There seems to be a relationship between what you are saying and one of the meanings of the word, ’salvation’.

K : ’Salvare’, to save.

A : To save.

K : To save.

A : To make whole.

K : To make whole. How can you be whole, sir, if you are hurt ?

A : Impossible.

K : Therefore it is tremendously important to understand this question.

A : Yes, it is. But I am thinking of a child who comes to school who has already got a freight car filled with hurts.

K : I know - hurts.

A : We are not dealing with a little one in the crib now, but we’re already...

K : We are already hurt.

A : Already hurt. And hurt because it is hurt. It multiplies endlessly.

K : Of course. From that hurt he’s violent. From that hurt he is frightened and therefore withdrawing. From that hurt he will do neurotic things. From that hurt he will accept anything that gives him safety - god, his idea of god is a god who will never hurt. (laughs)

A : Sometimes a distinction is made between ourselves and animals with respect to this problem. An animal, for instance, that has been badly hurt will be disposed toward everyone in terms of emergency and attack.

K : Attack, I know.

A : But over a period of time, it might take three or four years, if the animal is loved and...

K : So, sir, you see, you said, loved. We haven’t got that thing.

A : No.

K : And parents haven’t got love for their children. They may talk about love. Because the moment they compare the younger to the older they have hurt the child. ’Your father was so clever, you are such a stupid boy.’ There you have begun. In schools when they give you marks it is a hurt - not marks - it is a deliberate hurt. And that is stored, and from that there is violence, there is every kind of aggression, you know all that takes place. So a mind cannot be made whole, or is whole, unless this is understood very, very deeply.

A : The question that I had in mind before regarding what we have been saying is that this animal, if loved, will, provided we are not dealing with brain damage or something, will in time love in return. But the thought is that with the human person love cannot be in that sense coerced. It isn’t that one would coerce the animal to love, but that the animal, because innocent, does in time simply respond, accept.

K : Accept, of course.

A : But then a human person is doing something we don’t think the animal is.

K : No. The human being is being hurt and is hurting all the time.

A : Exactly. Exactly. While he is mulling over his hurt then he is likely to misinterpret the very act of generosity of love that is made toward him. So we are involved in something very frightful here : by the time the child comes into school, seven years old...

K : He is already gone, finished, tortured. There is the tragedy of it, sir, that is what I mean.

A : Yes, I know. And when you ask the question, as you have : is there a way to educate the child so that the child...

K : ...is never hurt. That is part of education, that is part of culture. Civilisation is hurting. Sir, look, you see this everywhere all over the world, this constant comparison, constant imitation, constant saying, you are that, I must be like you. I must be like Krishna, like Buddha, like Jesus - you follow ? That’s a hurt. Religions have hurt people.

A : The child is born to a hurt parent, sent to a school where it is taught by a hurt teacher. Now you are asking : is there a way to educate this child so that the child recovers.

K : I say it is possible, sir.

A : Yes, please.

K : That is, when the teacher realises, when the educator realises he is hurt and the child is hurt, he is aware of his hurt and he is aware also of the child’s hurt then the relationship changes. Then he will in the very act of teaching, mathematics, whatever it is, he is not only freeing himself from his hurt but also helping the child to be free of his hurt. After all that is education : to see that I, who am the teacher, I am hurt, I have gone through agonies of hurt, and I want to help that child not to be hurt, and he has come to the school being hurt. So I say, ’All right, we both are hurt, my friends, let us see, let’s help each other to wipe it out’. That is the act of love.

A : Comparing the human organism with the animal, I return to the question whether it is the case that this relationship to another human being must bring about this healing.

K : Obviously, sir, if relationship exists, we said relationship can only exist when there is no image between you and me.

A : Let us say that there is a teacher who has come to grips with this in himself, very, very deeply, has, as you put it, gone into the question deeper, deeper and deeper, has come to a place where he no longer is hurt-bound. The child that he meets or the young student that he meets, or even a student his own age, because we have adult education, is a person who is hurt-bound and will he not...

K : Transmit that hurt to another ?

A : No, will he not, because he is hurt-bound, be prone to misinterpret the activity of the one who is not hurt-bound ?

K : But there is no person who is not hurt-bound, except very, very few. Look, sir, lots of things have happened to me personally, I have never been hurt. I say this in all humility, in the real sense, I don’t know what it means to be hurt. Things have happened to me, people have done every kind of thing to me, praised me, flattered me, kicked me around, everything. It is possible. And as a teacher, as educator, to see the child, and it is my responsibility as an educator to see he is never hurt, not just teach some beastly subject. This is far more important.

A : I think I have some grasp of what you are talking about. I don’t think I could ever in my wildest dreams say that I have never been hurt. Though I do have difficulty, and have since a child - I have even been taken to task for it - of dwelling on it. I remember a colleague of mine once saying to me with some testiness when we were discussing a situation in which there was conflict in the faculty : ’Well, the trouble with you is you see, you can’t hate.’ And it was looked upon as a disorder in terms of being unable to make a focus towards the enemy in such a way as to devote total attention to that.

K : Sanity is taken for insanity.

A : Yes, so my reply to him was simply, ’Well that’s right and, we might as well face it, and I don’t intend to do anything about that’.

K : Quite, quite, quite.

A : But it didn’t help the situation in terms of the interrelationship.

K : So the question is then : in education can a teacher, educator, observe his hurts, become aware of them, and in his relationship with the student resolve his hurt and the student’s ? That’s one problem. It is possible if the teacher is really, in the deep sense of the word, educator, that is, cultivated. And the next question, sir, from that arises : is the mind capable of not being hurt, knowing it has been hurt ? Not add more hurts. Right ?

A : Yes.

K : I have these two problems : one, being hurt, that is the past ; and never to be hurt again. Which doesn’t mean I build a wall of resistance, that I withdraw, that I go off into a monastery, or become a drug addict, or some silly thing like that, but no hurt. Is that possible ? You see the two questions ? Now, what is hurt ? What is the thing that is hurt ? You follow ?

A : Yes.

K : We said the physical hurt is not the same as the psychological.

A : No.

K : So we are dealing with psychological hurt. What is the thing that is hurt ? The psyche ? The image which I have about myself ?

A : It is an investment that I have in it.

K : Yes, it’s my investment in myself.

A : Yes. I’ve divided myself off from myself.

K : Yes, in myself. That means, why should I invest in myself. What is ’myself’ ? You follow ?

A : Yes, I do.

K : In which I have to invest something. What is myself ? All the words, the names, the qualities, the education, the bank account, the furniture, the house, the hurts, all that is me.

A : In an attempt to answer the question : what is myself, I immediately must resort to all this stuff.

K : Obviously.

A : There isn’t any other way. And then I haven’t got it. Then I praise myself because I must be so marvellous as somehow to slip out.

K : Quite, quite. (both laugh)

A : I see what you mean. I was thinking just a moment back when you were saying it is possible for the teacher to come into relationship with the student so that a work of healing, or an act of healing happens.

K : See sir, this is what I would do if I were in a class, that’s the first thing I would begin with, not some subject. I would say, ’Look, you are hurt and I am hurt, we are both of us hurt’. And point out what hurt does, how it kills people, how it destroys people ; out of that there is violence, out of that there is brutality, out of that I want to hurt people. You follow ? All that comes in. I would spend ten minutes talking about that, every day, in different ways, till both of us see it. Then as an educator I will use the right word and the student will use the right word, there will be no gesture, there’ll be no irritation, we are both involved in it. But we don’t do that. The moment we come into class we pick up a book and there it goes off. If I was an educator, whether with the older people, or with the younger people, I would establish this relationship. That’s my duty, that’s my job, that’s my function, not just to transmit some information.

A : Yes, that’s really very profound. I think one of the reasons that what you have said is so difficult for an educator reared within the whole academic...

K : Yes, because we are so vain !

A : Exactly. We want not only to hear that it is possible for this transformation to take place, but we want it to be regarded as demonstrably proved and therefore not merely possible but predictably certain.

K : Certain, yes, we want a guarantee.

A : And then we are back into the whole thing.

K : Of course we are back into the old rotten stuff. Quite right.

A : Next time could we take up the relationship of love to this ?

K : Yes, we will.

A : I would very much enjoy that, and it would seem to me...

K : ...it will all come together.

A : Come together, in the gathering together.

Ndl : (La traduction finale a été légèrement modifiée)

Travail proposé par Jeannine Ballweg

« Voici la transcription sous Word de la traduction française de l’échange JK - DB - LA NATURE DE LA BLESSURE. »

"J’avais commencé ce travail après la semaine passée avec le Pr Krishna aux Houches (2003).

Quand je l’ai repris récemment, je me suis rendu compte que la traduction avait été depuis, améliorée."

Copyright Krishnamurti Foundation Trust LTD, 1974

Accès adhérents

Accès adhérents